Introduction :

Long before air conditioners and heaters, our ancestors crafted homes that worked in sync with nature. This approach, known as climate responsive design in vernacular architecture, uses local materials and age old techniques to create comfortable living spaces. They did it all by using minimal resources while creating a shelter that breathes, adapts and protects their habitat.

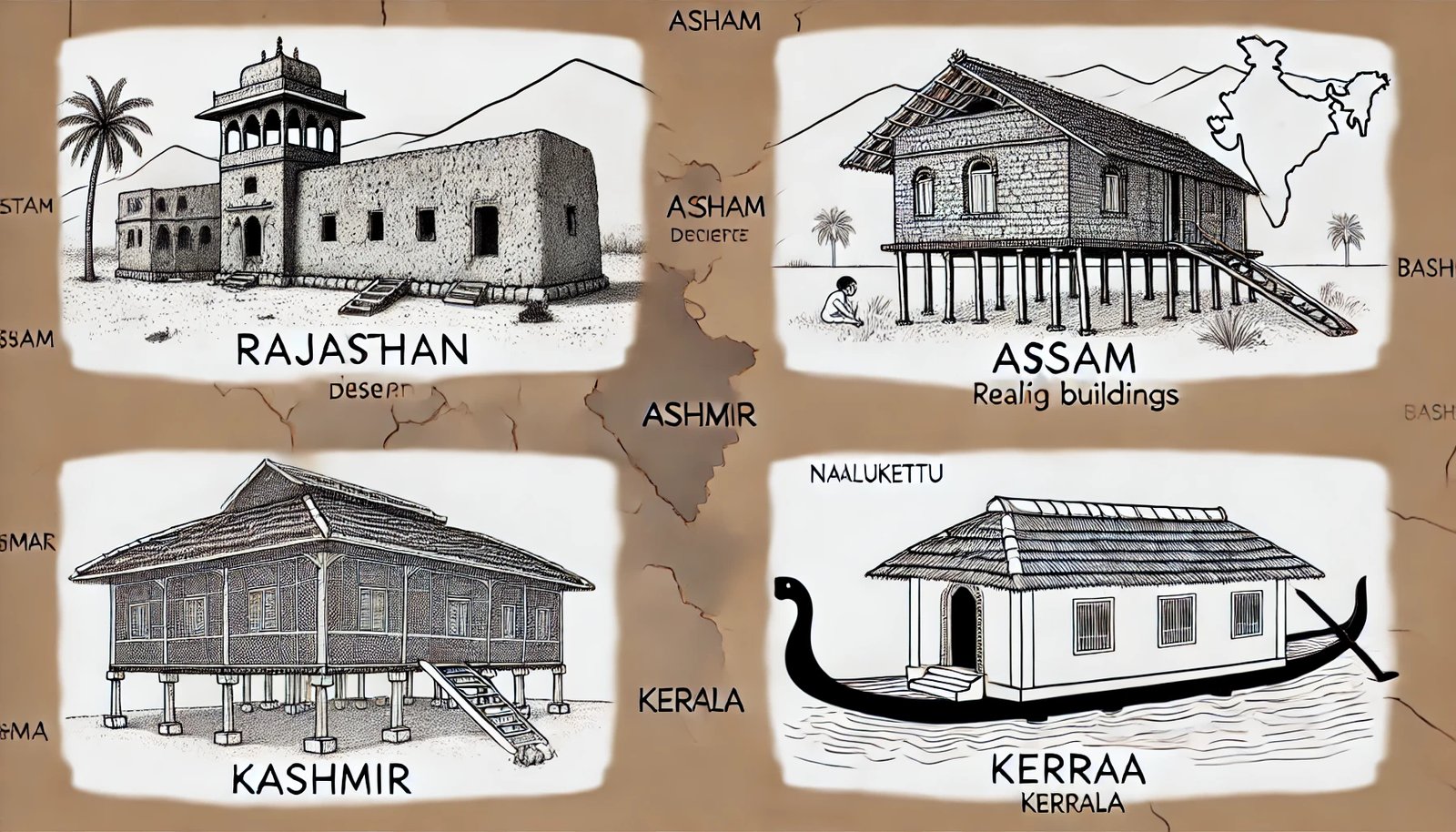

Let us look into a few examples of these traditional builders across India that outsmarted the elements of architecture.

Cool Caves of Rajasthan :

To survive in the scorching deserts of Rajasthan, some communities found an unexpected solution of underground homes. These structures that look like caves are known as ‘bhunga’. This helps in maintaining a steady temperature throughout the year while providing a cooling recess from the intense heat above.

Bhungas are typically circular structures that are partially dug into the earth. They have thick mud walls and domed roofs which act as great insulators. The circular shape minimizes exposure to sun and reduces the impact of wind. The earthen floor absorbs excess moisture and keeps the interiors dry and comfortable all the time.

Floating Homes of Kashmir :

The famous houseboats of Dal Lake are just picturesque and smart! These floating homes use the lake’s thermal mass to stay warm in winter and cool in summer while the wooden construction of these houseboats provide excellent insulation as well.

The design of these houseboats are known as the ‘doongas’. The wooden planks used in the construction expand when it’s wet and create a watertight seal. The sloped roofs allow an easy snow removal process during winters. The intricate woodwork in the interiors creates air pockets that further insulates the living space while making it look aesthetically pleasing as well.

The Breathing Home of Kerala :

In the humid climates of Kerala, traditional homes called ‘naalukettu’ use a clever design to keep the air flowing. High ceilings, open courtyards and strategically placed windows that create enough natural light and ventilation which helps in reducing humidity while keeping the interiors feel fresh.

The naalukettu’s layout typically features four blocks around a central courtyard which is known as the ‘nadumuttam’. This acts as the central cooling system of the house as it lets the hot air rise and escape, creating a low pressure area that draws in cooler air from the surrounding rooms. The sloped roofs here have overhanging eaves that act as a shade during summers and protection from the rain during monsoons.

The Ready Stilt Houses of Assam :

For a place like Assam, where earthquakes are prone in the area, livelihood can be pretty hard. However, the traditional stilt houses of Assam are life saviors as they are built to resist both earthquakes and floods.

These houses are known as ‘chang ghars’ with an elevated living area above flood levels. The main structure is built with a bamboo framework which is both strong and flexible that reduces the risk of collapse, keeping the inhabitants safe.

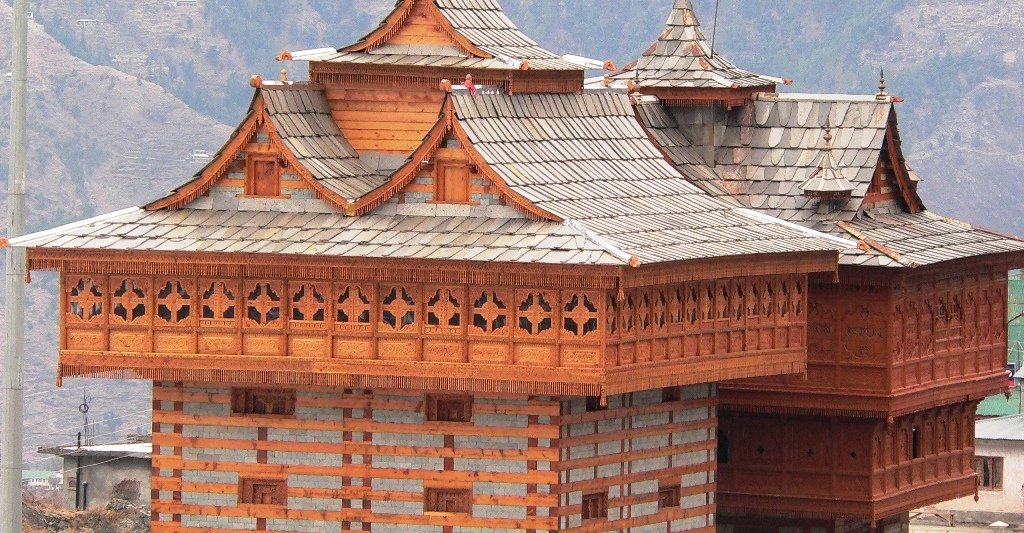

Mud Homes of Himachal Pradhesh :

In the freezing Himalayan region, ‘kath kuni’ architecture uses alternating layers of stone and wood and seals it with mud mortar. This combination traps heat efficiently that keeps the interiors warm even in the harsh mountain winters.

The kath kuni technique is a perfect example of making the most out of local materials. The stone provides thermal mass that absorbs heat during the day time and releases it slowly at night. The wood adds insulation and flexibility and the walls are usually about 2 feet thick which creates a substantial barrier against the cold. Small windows further minimize the heat loss and allow just enough light.

Conclusion :

As we face growing environmental challenges, there is so much that we can learn from these time tested traditional techniques that our ancestors made using simple, locally available materials.

The principles behind these vernacular designs – using local materials, working with the climate rather than against it, creating multi functional spaces – are all more relevant than ever. These techniques are an inspiration for modern architectures to develop sustainable structures using the traditional wisdom and combining it to the modern technology.

Bibliography :

Caritas India Chang ghar: A home to adapt to climate change. Retrieved from

https://caritasindia.org/GlobalProgramIndia/chang-ghar-a-home-to-adapt-to-climate-change/

Kader S. Vernacular Architecture Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/vernacular-architecture-238882581/238882581

Singh, D. Vernacular Architecture of Kashmir. Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/vernacular-architecture-of-kashmir/244806102

Urban Design Lab. Vernacular Architecture : Meaning and Examples. Retrieved from https://urbandesignlab.in/vernacular-architecture-meaning-examples/

Wikipedia. Kath kuni architecture. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kath_kuni_architecture

Wikipedia. Nalukettu. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/N%C4%81lukettu